“Gambling addiction has contributed to 184 suicides in Victoria over eight years, although the true figure could be much higher” www.theguardian.com/australia…

The pursuit of Aboriginal literary sovereignty

“Perhaps critique and analysis informed by the traditions and priorities of the settler colony can never register the full living and survivance of the oldest continuing culture on earth upon whose disappearance the success of the colony is predicated? Perhaps these traditions and priorities are unable to depart from the assumption of a right-to-know fundamentally incongruent with Aboriginal ontologies, which necessitate opacity and cultural sovereignty? Perhaps the answer is to withhold and to preserve our knowings for ourselves first and foremost?”

Reading and Speaking With - Evelyn Araluenon on the pursuit of Aboriginal literary sovereignty

Trilemma facing carbon extractive multinational corporations

“In this report, we have argued that Shell will face a trilemma with respect to these questions. It can achieve only a maximum of two out of three goals. The three goals Shell is aiming for can be described as:

Goal A continuing to operate as an oil and gas giant profiting from consuming ever greater portions of the global carbon budget; Goal B continuing to pursue high shareholder returns; and Goal C transforming itself into a major renewable energy player.

For a just transition, Shell can achieve only one of the three goals.”

Good insights in this report from SOMO - Stranded: Why Shell is unable to navigate the just transition trilemma

“offers insights into how NGOs play a critical role in stifling the development and independence of radical African movements”

“In Western philosophy the proper way is considered ethics, whereas in Aboriginal society, as far as it is known, there is no equivalent term for ethics, this is because proper action comes from the external order internalised through collective empirical observation over tens of thousands of years, rather than abstract individualist thinking.

The term ethics will be employed, but with the understanding that Aboriginal ethics encompasses more than simply applying principles of right action in order to know how to act.”

Really interesting article by Mary Graham on “The Law of Obligation, Aboriginal Ethics: Australia Becoming, Australia Dreaming”

“Rich people get lots of it.Poor people don’t get any of it!”: Fifty years of tackling the Inverse Care Law

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to speak at the South Western Sydney Local Health District Primary & Community Health Research & Innovation Showcase on 6 September 2023 about 50 years of the inverse care law.

My slides are at harrisroxashealth.com/2023/09/inversecare50/

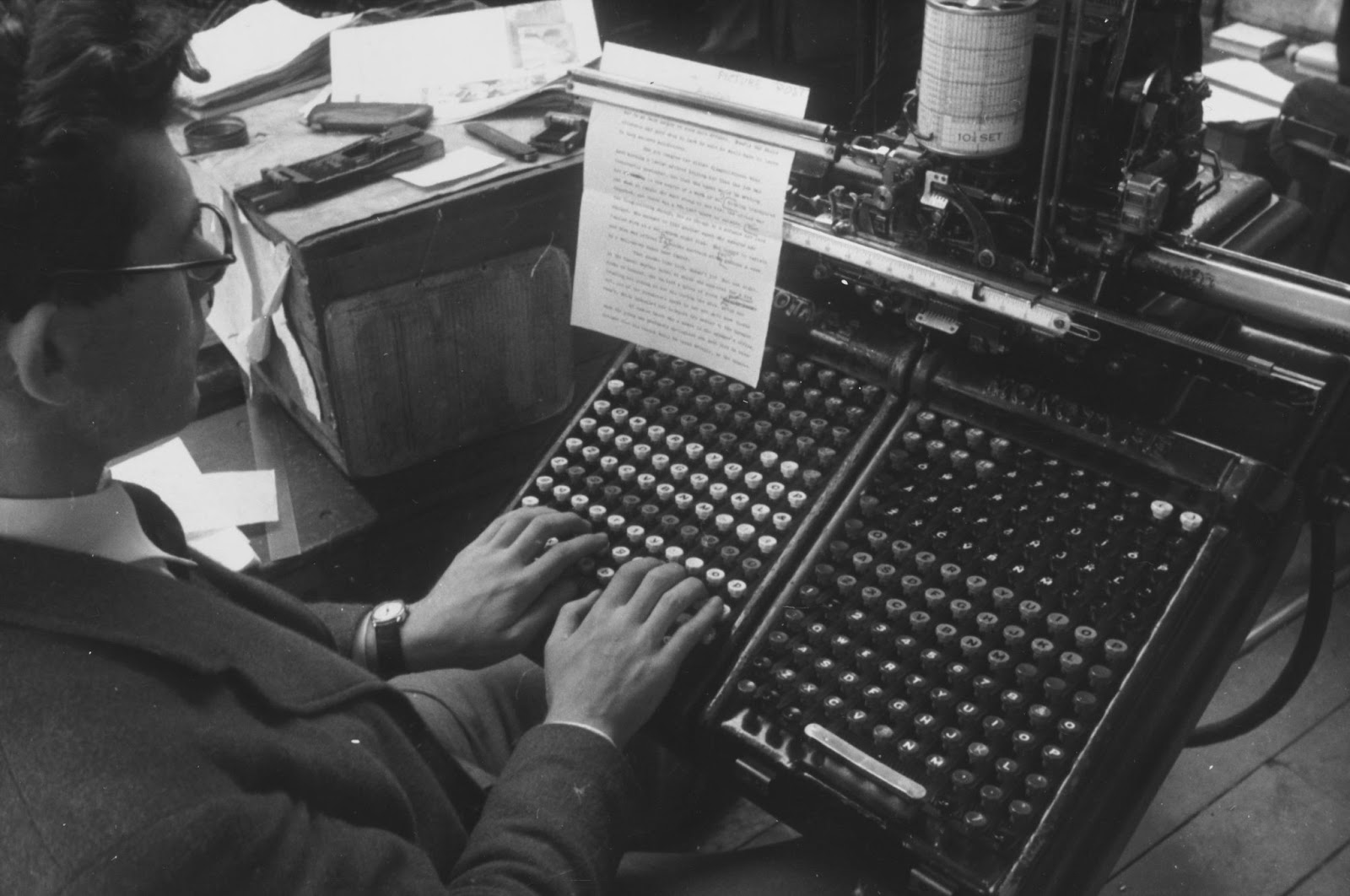

60 years old, the Yirrkala Bark Petitions are one of our founding documents – so why don’t we know more about them? - Prof Clare Wright

theconversation.com/friday-es…

Why engage in a deeper exploration of the creation of meaning when ChatGPT can do it for you?

I dread the garbage I’m going to be sent to review.

"Seeing humans and computers as interchangeable also meant that humans had begun to conceive of themselves as computers, and so to act like them"

“For Weizenbaum, judgment involves choices that are guided by values. These values are acquired through the course of our life experience and are necessarily qualitative: they cannot be captured in code. Calculation, by contrast, is quantitative. It uses a technical calculus to arrive at a decision. Computers are only capable of calculation, not judgment. This is because they are not human, which is to say, they do not have a human history – they were not born to mothers, they did not have a childhood, they do not inhabit human bodies or possess a human psyche with a human unconscious – and so do not have the basis from which to form values…

Seeing humans and computers as interchangeable also meant that humans had begun to conceive of themselves as computers, and so to act like them. They mechanised their rational faculties by abandoning judgment for calculation, mirroring the machine in whose reflection they saw themselves.”

Weizenbaum’s nightmares: how the inventor of the first chatbot turned against AI - The Guardian

Colonial science

European colonies became the frontiers of exploration, extraction and production of tropical plants. They also became captive markets for exports, where colonial states were able to establish monopolies and manipulate import-export taxes. The botanical sciences aided the colonial enterprise and were, in turn, organized by it. The Long Shadow Of Colonial Science

An interesting and worthwhile piece. I’ve been increasingly concerned that social research remains largely colonial in its outlook: an obsession with frontiers; ongoing extractivism (usually, but not solely, in terms of data); deep-rooted and largely uninterrogated beliefs that there should be a power imbalance between subjects and investigators.

We talk a big game in terms of decolonising and ethical practices but reality still falls a long way short.

Empire of dust

In 2019, a Financial Times investigation declared the London underground “the dirtiest place in the city”, with parts of the Central Line between Bond Street and Notting Hill Gate having more than eight times the WHO limit for PM2.5s. Tube dust is particularly high in iron oxide from the metal brakes and rails, but it’s not only mechanical. “A lot of the dust in this environment is coming from the passengers themselves,” Alno Lesch, operational manager for track cleaning, told the Financial Times, pulling out a black tangle from under the train platform. Human hair. Empire of dust: what the tiniest specks reveal about the world - The Guardian

All I can say is yikes.

Understand who this person was, who they are, their challenges, their triumphs: What leads to brilliant aged care?

Even though many aged care services don’t provide the care that older people and carers need and want, some do it much better than others. Why?

That’s the question colleagues from WSU, UNSW, SESLHD, SWSLHD, RCSI and I explored in an open access article that explores these questions, led by Associate Professor Ann Dadich.

Rather than focusing on the substantial and systemic problems facing aged care, this study examined brilliant aged care — practices that exceeded expectation.

There are many insights into what can lead to brilliant aged care, which can be broadly categorised into:

- deep understanding of the older person

- more than a job

- innovative practices

- permission to reprioritise.

Some of the best insights came from the artefacts that people were asked to bring to the interview, which were items (e.g. photos, items, artworks or other objects) that reflected brilliant aged care for them. These artefacts opened up new lines of discussion and new ideas, for example:

“people in the late stages of dementia are like an oyster, one of the ugliest, kind of gnarled shells you could possibly think of. There are so many beautiful shells in the world. The oyster isn’t one of them and yet when you open it up, it has this extraordinary little pearl inside it and that’s what we need to find in every older person. Every older person, no matter … what their state of health or wellbeing, still has that pearl that is that beautiful human being inside them and it’s our job, not their job, it’s our job to open that up and find that pearl.” (Grace)

There’s a lot more in the open access article – take a look.

Dadich, A., Kearns, R., Harris-Roxas, B., Ni Chroinin, D., Boydell, K., Ní Shé, É., Lim, D., Gonski, P., & Kohler, F. (2023). What constitutes brilliant aged care? A qualitative study of practices that exceed expectation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, online first. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16789

“subsea cables are the workhorses of global commerce and communications, carrying more than 99% of traffic between continents” The Secret Life of the 500+ Cables That Run the Internet - CNET

How Monotype became a font behemoth

On the enshittefication of fonts.

That optimism, however, will likely be tested as Monotype begins dabbling with AI. The company already owns WhatTheFont, an app that uses deep learning to identify fonts from photographs, and it’s added an AI-powered font-pairing feature.

Monotype says it plans to use machine learning and AI to improve how users discover new fonts on its platform — an innovation that will undoubtedly affect foundries, though it remains to be seen exactly how.

Where do fonts come from? This one business, mostly - The Hustle