Imagining a better future: What I learned from solarpunk films

One of my holiday projects has been to attempt to compile a comprehensive list of solarpunk films. You can see the whole list here - it’s currently 37 movies and growing.

I was expecting it to be a fairly straightforward task. There can’t be that many solarpunk movies after all. Instead it was a conceptually tricky and profoundly moving process.

These films have taken me in a few weird directions, and gave me insights into how we might tell better, more creative, energising, and ultimately more optimistic stories about our future.

Solar…what?

Before continuing it’s probably worth defining terms: what makes a movie a solarpunk film? It seems like a simple question. At first I thought it was just a matter of identifying films that depict better futures with added urban jungle vibes. But that’s simultaneously too broad and not specific enough.

Instead I ended up making a list of ingredients in my notes app as I watched. All the films on my list feature at least two of these ingredients, and most have four or more:

- Ecological restoration: environmental damage being healed through patience, technological innovation that integrates rather than displaces, community mobilising, or through nature's own resilience.

- Harmony between nature and technology: societies that integrate green spaces, renewable energy, and appropriate technology rather than dominating or destroying ecosystems.

- Community-focused solutions: collective action, participatory governance (rather than democracy per se), and people suporting each other winning out over individual heroism or authoritarianism.

- Hopeful futures: even amid crisis or collapse, paths forward exist through cooperation, ingenuity, and transformed relationships with each other and the natural world

- Decentralisation of power: innovation emerges in bottom-up ways more than through technocracy or rarified expertise, resistant is grassroots, and corporate monopolies and centralised power by localised systems and control.

- Do it yourself/maker culture**: creation by skilled craftspeople and artisans doing meaningful work, there’s creative repurposing of existing goods, and tools are accessible.

The patterns I observed

Japanese animation propelled the development of solarpunk concepts and aesthetics

Studio Ghibli films, specifically those directed by Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, established both the aesthetics and the themes that define solarpunk cinema. This draws on deeper cultural contexts:

- the Shinto tradition of animism (kami inhabiting natural phenomena),

- the concepts related to satoyama and harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, and

- Japan's postwar reckoning with the human and ecological toll of industrialisation and militarism.

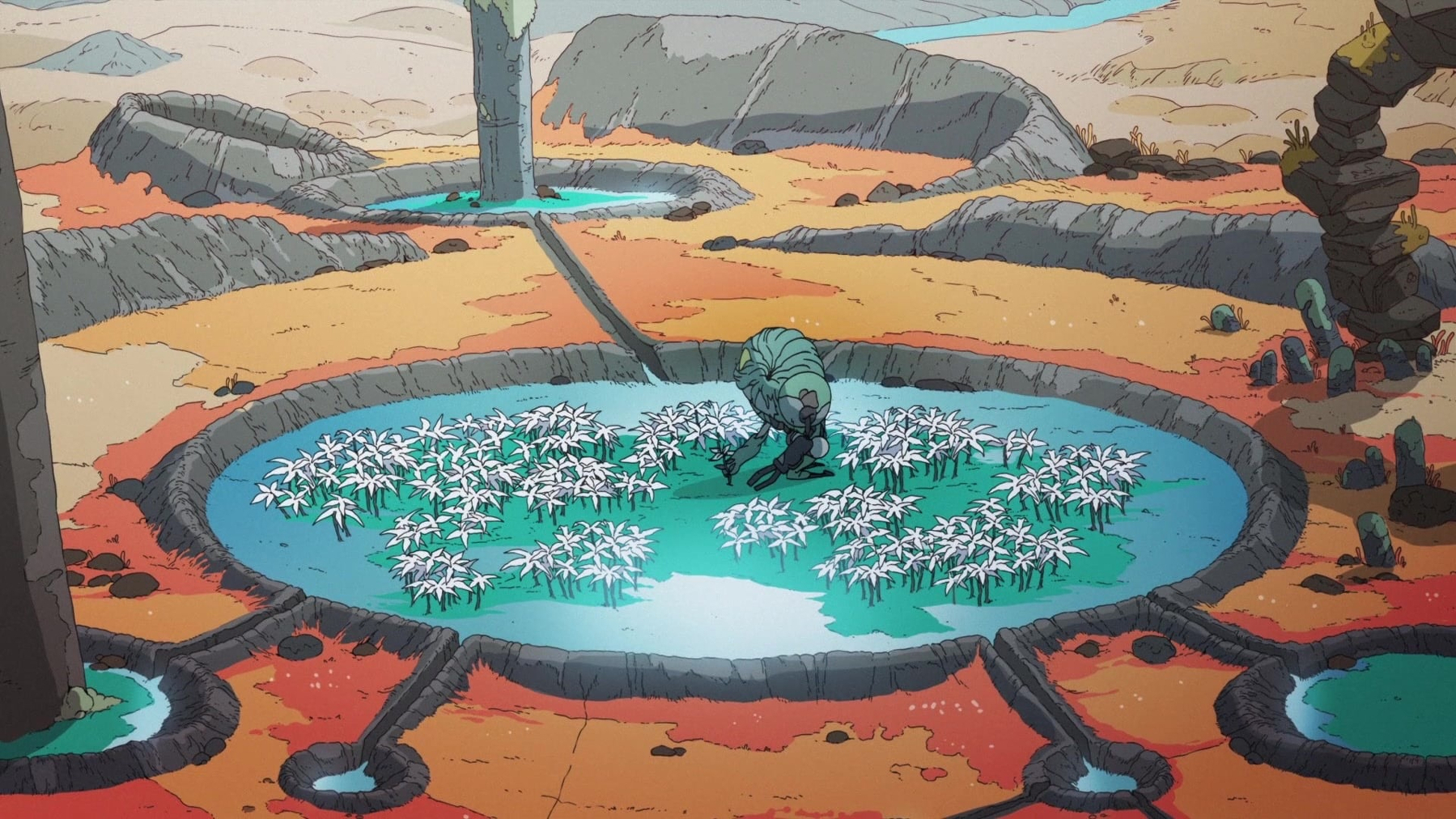

Miyazaki's films don't simply depict nature as backdrop but as active a participant in the world and stories. For example the Forest Spirit in Princess Mononoke, the Toxic Jungle's purification of the environment in Nausicaä, and Totoro's ancient camphor tree all have agency and act to make changes in their stories. This fusion of environmentalism with spiritualism created a cinematic language for ecological hope that Western animation (and Western society) has only recently begun to explore.

The influence extends beyond themes to aesthetics as well. Ghibli's signature elements of wind-powered technology, minimally disruptive flight, moss-covered ruins reclaiming human artifice, and pastoral landscapes punctuated by technology rather than overwhelmed by it. This had all become the visual language of solarpunk long before the movement had a name, due to Ghibli. When contemporary solarpunk writers talk about "green cities" and "nature integrated with infrastructure" they're invoking the imagery that was rendered in Castle in the Sky's Laputa or Origin: Spirits of the Past's Neutral City decades earlier.

Ecological restoration drives the plot but also gives the films their moral core

The most consistent solarpunk element in films is the possibility of environmental healing. This represents a fundamental philosophical stance, that is, environmental damage is neither inevitable nor irreversible. These films insist that healing remains possible, and can take the form of patient individual action (Elzéard Bouffier's patient tree planting in The Man Who Planted Trees), technological innovation, community mobilisation, or the (re)discovery of nature's own restorative power (e.g. Nausicaä learning the Toxic Jungle purifies soil),

This restoration imperative always requires epistemological transformation. Characters must learn to see the world differently first. Nausicaä discovers the jungle isn't toxic but healing. The people of Avalonia in Strange World realise their power source is parasitic. Mija in Okja has to convince others to see Okja not as an animal to exploit but a sentient being.

Through this process restoring the environment restores our moral centre. Characters and humanity must transform how we understand our relationship with nature before we can transform ourselves.

Importantly solarpunk films rarely depict returning to some notionally pristine pre-human state. Instead they imagine new equilibriums. Humans and the Toxic Jungle coexisting in Nausicaä. Humans and machines building IO together in The Matrix Resurrections. Tokyo adapting to permanent flooding in Weathering with You. The goal isn't untouched or fictional wildernesses but sustainable integration.

Technology can be a tool shaped by intention, not force

Unlike cyberpunk's reflexive technophobia, where technology invariably serves corporate control and leads to human alienation, solarpunk cinema presents technology as more morally neutral. Its effects are determined by purpose and its governance.

The same technological capability appears in radically different contexts. For example robots can be corporate exploitation machines (Elysium's enforcement robots - not a solarpunk film on my list, but maybe it should be because of the gritty DIY vibe and optimistic ending) or gentle caretakers (Castle in the Sky's garden-tending automata). Genetic engineering produces both Mirando's factory-farmed Okja and the possibility of breaking seed monopolies in Vesper. Artificial intelligence can enforce conformity (City of Ember's corrupt mayor) or enable liberation (The Matrix Resurrections' synthients).

The determining factor is almost always depicted as being governance structures and social values. Decentralised, community-controlled technology is shown to serve human and ecological flourishing. For example Neutral City's negotiated coexistence with the sentient Forest, Wakanda's vibranium research being shared for global benefit, or the wind turbines in The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind controlled by villagers they serve. In contrast profit-driven technology is only ever extractive. Mirando Corporation or Buy-n-Large's earth-wrecking consumerism.

This creates a pattern I noticed early on: protagonists don't reject technology but redirect and divert it. Vesper doesn't destroy biotech but liberates it from monopolistic control. The Avalonians don't abandon progress but shift from parasitic Pando to wind power.

The punk in solarpunk comes not through rejection of technology but through collective seizure of it. Technology for the many, not the few.

Community over individuals, collaboration over conquest

All films require protagonists to drive narratives forward structurally, but I was struck that solarpunk cinema consistently emphasises that meaningful change emerges through collective action rather than individual heroics. Even when central characters succeed they depend on building coalitions and mobilising communities. Think of Nausicaä uniting kingdoms and forest spirits, Mija joining with the Animal Liberation Front, and even Bacurau's villagers share knowledge across generations to resist invasion.

This collectivism extends to the depiction of aspirational governance structures. Pom Poko's tanuki hold democratic councils to debate resistance strategies. La Belle Verte's inhabitants use participatory assemblies to make planetary decisions. Neutral City in Origin negotiates terms with the sentient forest rather than attempting to dominate it.

Even in films that show flawed or more complex communities (think Iron Town's environmentally destructive mining in Princess Mononoke), they demonstrate communal social values. Lady Eboshi's settlement provides refuge for lepers and former sex workers. This is at the core of solarpunk's insistence that social and environmental justice must advance together.

The emphasis on community serves practical and ideological functions. Practically, environmental challenges exist at scales beyond the individual. Restoring an ecosystem, transitioning energy systems, or defending against exploitation requires coordination. Ideologically, community itself becomes the vaccine to the atomisation and alienation that enables environmental destruction. When WALL-E's humans return to Earth, they don't arrive as isolated consumers but as a rekindled community ready to work together.

Crisis is an opportunity, not the end

A lot of solarpunk films begin during environmental devastation or social collapse. Examples include WALL-E's garbage-buried Earth, Vesper's post-collapse world of seed monopolies, Nausicaä's spreading Toxic Jungle, and Pumzi's underground rationing after the Water War. This distinguishes solarpunk films from both pure utopias and pure dystopias. The frequent narrative arc from dystopia-to-hope acknowledges crises while insisting on the possibility of a better future.

This is more than upbeat plotting, it seems to do important work to advance the genre’s central argument. It says "yes, things are bad and we can still work towards something better." The catastrophes represented often arise from the very systems solarpunk opposes (to wit: WALL-E's consumerism, Strange World's parasitic energy extraction). These systems caused the crisis, different systems are needed to resolve it. Wind turbines replacing Pando, humans and robots collaborating in restoration, communities sharing resources rather than hoarding them.

Importantly the "hope" in these story arcs doesn't mean easy resolution. Princess Mononoke ends with the Forest Spirit dead even as the land regenerates. Weathering with You accepts a permanently flooded Tokyo rather than achieving restoration. Bacurau's villagers defeat their immediate attackers but remain at the margins of a hostile larger society. The Matrix Resurrections liberates Neo and Trinity but leaves most of humanity trapped. This more tempered resolution differentiates solarpunk's hope from pollyanna-like optimism. Transformation is possible but requires ongoing work, sacrifice, and acknowledgement that the work is never complete.

Indigenous ecological knowledge and decolonisation

A significant thread across solarpunk films - particularly in non-Western cinema and Afrofuturist works - focuses on indigenous knowledge systems and critiques colonial exploitation. Bacurau has a Brazilian lens, showing a sertão community with solar panels and collective governance resisting neo-colonial violence. Black Panther imagines what an African nation might have become without colonisation. Wakanda's vibranium technology develops from indigenous knowledge systems that were never derailed by European exploitation. Even films set in more fantastical contexts often incorporate this dynamic. Atlantis: The Lost Empire contrasts Atlantean traditional ways of working with American mercenary exploitation, while Moana deals with Polynesian navigation traditions.

This pattern aligns with broader solarpunk’s integration of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which recognises that many indigenous and pre-industrial societies developed sustainable practices that industrial capitalism destroyed or dismissed. The films on the list suggest that moving forward requires recovering and respecting Indigenous knowledge systems. The punk element here operates through decolonial ways of working - essentially rejecting the assumption that Western techno-science holds all answers.

The aesthetics of abundance and organic technology

Visually solarpunk films have cultivates a distinct aesthetic that’s really in contact to cyberpunk's neon decay and post-apocalyptic wastelands. Instead I consistently saw verdancy and abundance (and abundance in a genuine, non-Ezra Klein sense). This greenness and fertility serves practical and symbolic functions by demonstrating that societies can integrate nature in productive ways, and by showing that sustainability enables abundance rather than scarcity.

The integration of the practical and symbolic extends to architecture and technology. Rather than nature being separate zones, solarpunk films show buildings with plants growing on every surface (Olympus in Appleseed), settlements built around trees (Motunui in Moana), and technology that mimics organic forms (Atlantis' bioluminescent power systems). This may be the central aestheticof solarpunk - dichotomy between human/technological and natural realms is an artifice, they can merge and integrate.

Art Nouveau influences appear throughout the films, arising principally from Ghibli's curvilinear designs. Art Nouveau emerged during early industrial modernity, partly as a reaction against mechanical mass production toward more organic forms and artisanal crafts. Responses later echoed by solarpunk.

Social justice is inseparable from environmental justice

Perhaps the most consistent idea across solarpunk films is a refusal to separate environmental and social concerns. Films that imagine ecological restoration almost always pair it with fairer societies, while ecologically destructive societies are consistently oppressive hierarchies.

This pattern reflects solarpunk's roots in environmentalism and social justice. The films collectively argue that extractive capitalism, colonialism, and authoritarian control inevitably produce social oppression, because these all come from the warped internal logic of domination and hierarchy. Conversely, decentralised, participatory governance, and community-focused problem-solving enables more just relationships.

The expansion of solarpunk possibilities

Recent solarpunk cinema increasingly inhabits different genres beyond science fiction. Action in the case of Black Panther, adventure in Moana, magical realism in Beasts of the Southern Wild, horror(ish) in Love and Monsters, political thriller in Woman at War, even musical in Neptune Frost. Solarpunk values are starting to permeate broader forms of cinema but also other forms of expression.

This demonstrates solarpunk’s flexibility and relevance. A Malawian biographical drama about building a windmill, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, embodies solarpunk values just as fully as Japanese animated science fiction like Origin: Spirits of the Past. A Brazilian (decidedly weird) Western (Bacurau) and an Icelandic character study (Woman at War) both engage with solarpunk’s core concerns of community resilience, appropriate technology, resisting exploitation, and hope in culturally specific ways.

What I learned

Watching these films made me recognise there are more than aesthetic trends going on. There’s a coherent, if hidden, philosophy about how to navigate crises and build better futures. The principles that I could discern that might be relevant for what I do are:

- Restoration, not perfection. We don't need fully-formed solutions before acting. Like Bouffier planting acorns, small consistent actions compound over time.

- Community over heroics. Adopt more genuine collaborative approaches, things like participatory decision-making, co-design, recognising that complex challenges require coordination.

- Redirect technology, don't (necessarily) reject it. Rather than prohibiting AI or conversely accepting surveillance capitalism uncritically, we need to interrogate who controls technology, who benefits, and how we can redirect it toward fairness. The question isn't necessarily “should we use tech?” but "how do we ensure tech serves communities?" And if it doesn’t serve us, we should definitely bin it.

- Coexistence over false binaries. Resist simplistic either/or framing like centralised versus decentralised, individuals versus populations, scientific evidence versus lived experience. The goal is an achievable and sustainable equilibrium, not being right or victorious.

- Justice and sustainability. Attend to power, colonialism, and structural oppression - not as add-ons but as central to understanding and addressing challenges.

These films aren't escapist fantasy. They're imaginative rehearsals for futures we could actually build, if we keep these principles at the forefront of how we think and act. Optimism isn't naivety about how bad things are, but insistence that transformation remains possible through collective action and relationships. As someone who teaches people who shape health systems and who researches health equity, that's the kind of hope I need to sustain myself - and the hope I want to help others cultivate too.

The climate emergency is intensifying, social inequities continue to deepen, and systems of care are under ever more strain.

And yet.

Humans and robots plant gardens together. Communities resist expansionist extractivism and build alternatives. Young people undermine monopolies. The enterprise is never complete, the endpoint is never guaranteed, but the possibility of a better future persists. That's solarpunk's essential message, and it's one I'm going to carry forward.

Read the Solarpunk films list on Letterboxd

This post first appeared on Harris-Roxas Health