Posts

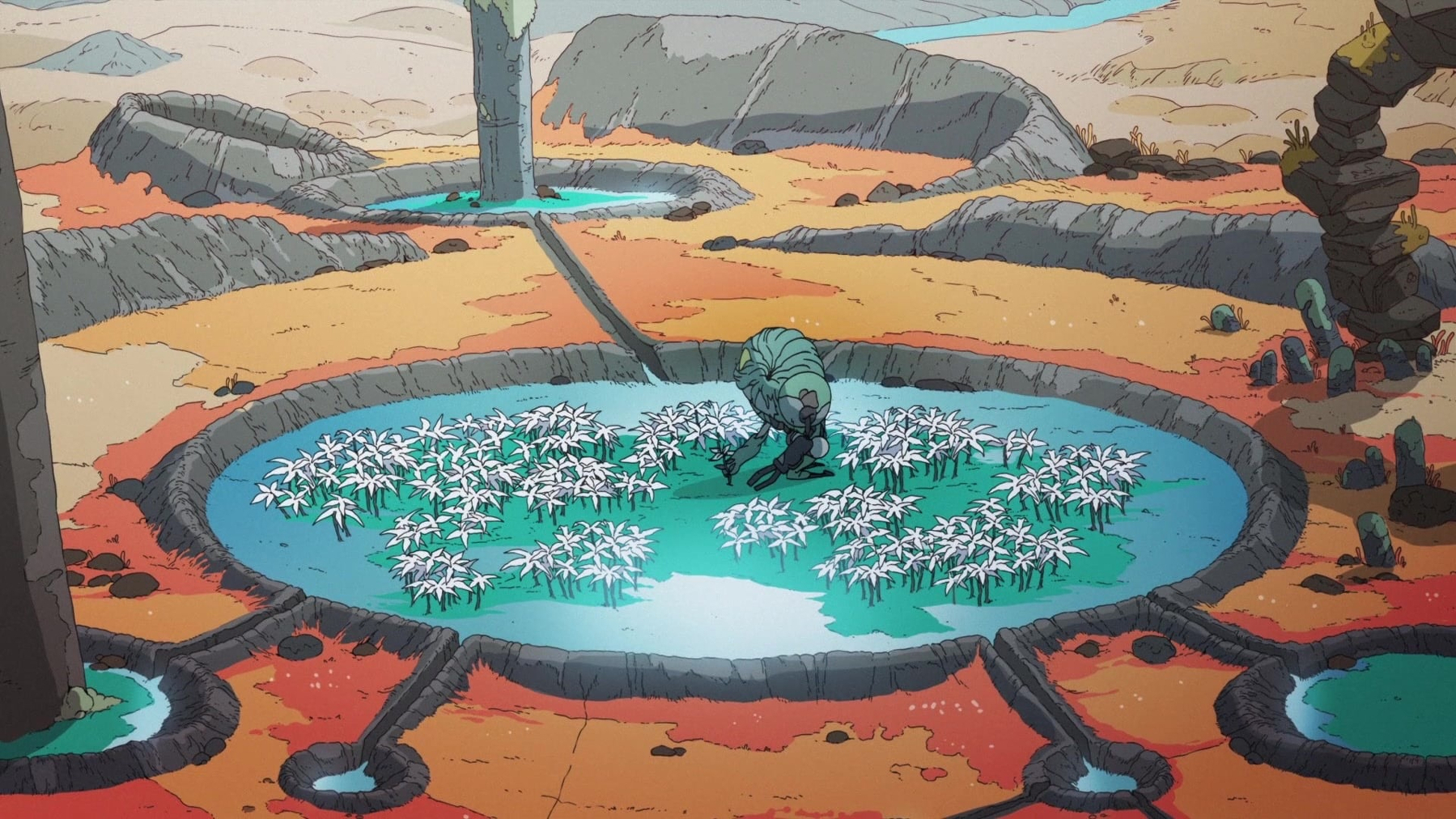

Imagining a better future: What I learned from solarpunk films

One of my holiday projects has been to attempt to compile a comprehensive list of solarpunk films. You can see the whole list here - it’s currently 37 movies and growing.

I was expecting it to be a fairly straightforward task. There can’t be that many solarpunk movies after all. Instead it was a conceptually tricky and profoundly moving process.

These films have taken me in a few weird directions, and gave me insights into how we might tell better, more creative, energising, and ultimately more optimistic stories about our future.

Solar…what?

Before continuing it’s probably worth defining terms: what makes a movie a solarpunk film? It seems like a simple question. At first I thought it was just a matter of identifying films that depict better futures with added urban jungle vibes. But that’s simultaneously too broad and not specific enough.

Instead I ended up making a list of ingredients in my notes app as I watched. All the films on my list feature at least two of these ingredients, and most have four or more:

- Ecological restoration: environmental damage being healed through patience, technological innovation that integrates rather than displaces, community mobilising, or through nature's own resilience.

- Harmony between nature and technology: societies that integrate green spaces, renewable energy, and appropriate technology rather than dominating or destroying ecosystems.

- Community-focused solutions: collective action, participatory governance (rather than democracy per se), and people suporting each other winning out over individual heroism or authoritarianism.

- Hopeful futures: even amid crisis or collapse, paths forward exist through cooperation, ingenuity, and transformed relationships with each other and the natural world

- Decentralisation of power: innovation emerges in bottom-up ways more than through technocracy or rarified expertise, resistant is grassroots, and corporate monopolies and centralised power by localised systems and control.

- Do it yourself/maker culture**: creation by skilled craftspeople and artisans doing meaningful work, there’s creative repurposing of existing goods, and tools are accessible.

The patterns I observed

Japanese animation propelled the development of solarpunk concepts and aesthetics

Studio Ghibli films, specifically those directed by Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, established both the aesthetics and the themes that define solarpunk cinema. This draws on deeper cultural contexts:

- the Shinto tradition of animism (kami inhabiting natural phenomena),

- the concepts related to satoyama and harmonious coexistence between humans and nature, and

- Japan's postwar reckoning with the human and ecological toll of industrialisation and militarism.

Miyazaki's films don't simply depict nature as backdrop but as active a participant in the world and stories. For example the Forest Spirit in Princess Mononoke, the Toxic Jungle's purification of the environment in Nausicaä, and Totoro's ancient camphor tree all have agency and act to make changes in their stories. This fusion of environmentalism with spiritualism created a cinematic language for ecological hope that Western animation (and Western society) has only recently begun to explore.

The influence extends beyond themes to aesthetics as well. Ghibli's signature elements of wind-powered technology, minimally disruptive flight, moss-covered ruins reclaiming human artifice, and pastoral landscapes punctuated by technology rather than overwhelmed by it. This had all become the visual language of solarpunk long before the movement had a name, due to Ghibli. When contemporary solarpunk writers talk about "green cities" and "nature integrated with infrastructure" they're invoking the imagery that was rendered in Castle in the Sky's Laputa or Origin: Spirits of the Past's Neutral City decades earlier.

Ecological restoration drives the plot but also gives the films their moral core

The most consistent solarpunk element in films is the possibility of environmental healing. This represents a fundamental philosophical stance, that is, environmental damage is neither inevitable nor irreversible. These films insist that healing remains possible, and can take the form of patient individual action (Elzéard Bouffier's patient tree planting in The Man Who Planted Trees), technological innovation, community mobilisation, or the (re)discovery of nature's own restorative power (e.g. Nausicaä learning the Toxic Jungle purifies soil),

This restoration imperative always requires epistemological transformation. Characters must learn to see the world differently first. Nausicaä discovers the jungle isn't toxic but healing. The people of Avalonia in Strange World realise their power source is parasitic. Mija in Okja has to convince others to see Okja not as an animal to exploit but a sentient being.

Through this process restoring the environment restores our moral centre. Characters and humanity must transform how we understand our relationship with nature before we can transform ourselves.

Importantly solarpunk films rarely depict returning to some notionally pristine pre-human state. Instead they imagine new equilibriums. Humans and the Toxic Jungle coexisting in Nausicaä. Humans and machines building IO together in The Matrix Resurrections. Tokyo adapting to permanent flooding in Weathering with You. The goal isn't untouched or fictional wildernesses but sustainable integration.

Technology can be a tool shaped by intention, not force

Unlike cyberpunk's reflexive technophobia, where technology invariably serves corporate control and leads to human alienation, solarpunk cinema presents technology as more morally neutral. Its effects are determined by purpose and its governance.

The same technological capability appears in radically different contexts. For example robots can be corporate exploitation machines (Elysium's enforcement robots - not a solarpunk film on my list, but maybe it should be because of the gritty DIY vibe and optimistic ending) or gentle caretakers (Castle in the Sky's garden-tending automata). Genetic engineering produces both Mirando's factory-farmed Okja and the possibility of breaking seed monopolies in Vesper. Artificial intelligence can enforce conformity (City of Ember's corrupt mayor) or enable liberation (The Matrix Resurrections' synthients).

The determining factor is almost always depicted as being governance structures and social values. Decentralised, community-controlled technology is shown to serve human and ecological flourishing. For example Neutral City's negotiated coexistence with the sentient Forest, Wakanda's vibranium research being shared for global benefit, or the wind turbines in The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind controlled by villagers they serve. In contrast profit-driven technology is only ever extractive. Mirando Corporation or Buy-n-Large's earth-wrecking consumerism.

This creates a pattern I noticed early on: protagonists don't reject technology but redirect and divert it. Vesper doesn't destroy biotech but liberates it from monopolistic control. The Avalonians don't abandon progress but shift from parasitic Pando to wind power.

The punk in solarpunk comes not through rejection of technology but through collective seizure of it. Technology for the many, not the few.

Community over individuals, collaboration over conquest

All films require protagonists to drive narratives forward structurally, but I was struck that solarpunk cinema consistently emphasises that meaningful change emerges through collective action rather than individual heroics. Even when central characters succeed they depend on building coalitions and mobilising communities. Think of Nausicaä uniting kingdoms and forest spirits, Mija joining with the Animal Liberation Front, and even Bacurau's villagers share knowledge across generations to resist invasion.

This collectivism extends to the depiction of aspirational governance structures. Pom Poko's tanuki hold democratic councils to debate resistance strategies. La Belle Verte's inhabitants use participatory assemblies to make planetary decisions. Neutral City in Origin negotiates terms with the sentient forest rather than attempting to dominate it.

Even in films that show flawed or more complex communities (think Iron Town's environmentally destructive mining in Princess Mononoke), they demonstrate communal social values. Lady Eboshi's settlement provides refuge for lepers and former sex workers. This is at the core of solarpunk's insistence that social and environmental justice must advance together.

The emphasis on community serves practical and ideological functions. Practically, environmental challenges exist at scales beyond the individual. Restoring an ecosystem, transitioning energy systems, or defending against exploitation requires coordination. Ideologically, community itself becomes the vaccine to the atomisation and alienation that enables environmental destruction. When WALL-E's humans return to Earth, they don't arrive as isolated consumers but as a rekindled community ready to work together.

Crisis is an opportunity, not the end

A lot of solarpunk films begin during environmental devastation or social collapse. Examples include WALL-E's garbage-buried Earth, Vesper's post-collapse world of seed monopolies, Nausicaä's spreading Toxic Jungle, and Pumzi's underground rationing after the Water War. This distinguishes solarpunk films from both pure utopias and pure dystopias. The frequent narrative arc from dystopia-to-hope acknowledges crises while insisting on the possibility of a better future.

This is more than upbeat plotting, it seems to do important work to advance the genre’s central argument. It says "yes, things are bad and we can still work towards something better." The catastrophes represented often arise from the very systems solarpunk opposes (to wit: WALL-E's consumerism, Strange World's parasitic energy extraction). These systems caused the crisis, different systems are needed to resolve it. Wind turbines replacing Pando, humans and robots collaborating in restoration, communities sharing resources rather than hoarding them.

Importantly the "hope" in these story arcs doesn't mean easy resolution. Princess Mononoke ends with the Forest Spirit dead even as the land regenerates. Weathering with You accepts a permanently flooded Tokyo rather than achieving restoration. Bacurau's villagers defeat their immediate attackers but remain at the margins of a hostile larger society. The Matrix Resurrections liberates Neo and Trinity but leaves most of humanity trapped. This more tempered resolution differentiates solarpunk's hope from pollyanna-like optimism. Transformation is possible but requires ongoing work, sacrifice, and acknowledgement that the work is never complete.

Indigenous ecological knowledge and decolonisation

A significant thread across solarpunk films - particularly in non-Western cinema and Afrofuturist works - focuses on indigenous knowledge systems and critiques colonial exploitation. Bacurau has a Brazilian lens, showing a sertão community with solar panels and collective governance resisting neo-colonial violence. Black Panther imagines what an African nation might have become without colonisation. Wakanda's vibranium technology develops from indigenous knowledge systems that were never derailed by European exploitation. Even films set in more fantastical contexts often incorporate this dynamic. Atlantis: The Lost Empire contrasts Atlantean traditional ways of working with American mercenary exploitation, while Moana deals with Polynesian navigation traditions.

This pattern aligns with broader solarpunk’s integration of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which recognises that many indigenous and pre-industrial societies developed sustainable practices that industrial capitalism destroyed or dismissed. The films on the list suggest that moving forward requires recovering and respecting Indigenous knowledge systems. The punk element here operates through decolonial ways of working - essentially rejecting the assumption that Western techno-science holds all answers.

The aesthetics of abundance and organic technology

Visually solarpunk films have cultivates a distinct aesthetic that’s really in contact to cyberpunk's neon decay and post-apocalyptic wastelands. Instead I consistently saw verdancy and abundance (and abundance in a genuine, non-Ezra Klein sense). This greenness and fertility serves practical and symbolic functions by demonstrating that societies can integrate nature in productive ways, and by showing that sustainability enables abundance rather than scarcity.

The integration of the practical and symbolic extends to architecture and technology. Rather than nature being separate zones, solarpunk films show buildings with plants growing on every surface (Olympus in Appleseed), settlements built around trees (Motunui in Moana), and technology that mimics organic forms (Atlantis' bioluminescent power systems). This may be the central aestheticof solarpunk - dichotomy between human/technological and natural realms is an artifice, they can merge and integrate.

Art Nouveau influences appear throughout the films, arising principally from Ghibli's curvilinear designs. Art Nouveau emerged during early industrial modernity, partly as a reaction against mechanical mass production toward more organic forms and artisanal crafts. Responses later echoed by solarpunk.

Social justice is inseparable from environmental justice

Perhaps the most consistent idea across solarpunk films is a refusal to separate environmental and social concerns. Films that imagine ecological restoration almost always pair it with fairer societies, while ecologically destructive societies are consistently oppressive hierarchies.

This pattern reflects solarpunk's roots in environmentalism and social justice. The films collectively argue that extractive capitalism, colonialism, and authoritarian control inevitably produce social oppression, because these all come from the warped internal logic of domination and hierarchy. Conversely, decentralised, participatory governance, and community-focused problem-solving enables more just relationships.

The expansion of solarpunk possibilities

Recent solarpunk cinema increasingly inhabits different genres beyond science fiction. Action in the case of Black Panther, adventure in Moana, magical realism in Beasts of the Southern Wild, horror(ish) in Love and Monsters, political thriller in Woman at War, even musical in Neptune Frost. Solarpunk values are starting to permeate broader forms of cinema but also other forms of expression.

This demonstrates solarpunk’s flexibility and relevance. A Malawian biographical drama about building a windmill, The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, embodies solarpunk values just as fully as Japanese animated science fiction like Origin: Spirits of the Past. A Brazilian (decidedly weird) Western (Bacurau) and an Icelandic character study (Woman at War) both engage with solarpunk’s core concerns of community resilience, appropriate technology, resisting exploitation, and hope in culturally specific ways.

What I learned

Watching these films made me recognise there are more than aesthetic trends going on. There’s a coherent, if hidden, philosophy about how to navigate crises and build better futures. The principles that I could discern that might be relevant for what I do are:

- Restoration, not perfection. We don't need fully-formed solutions before acting. Like Bouffier planting acorns, small consistent actions compound over time.

- Community over heroics. Adopt more genuine collaborative approaches, things like participatory decision-making, co-design, recognising that complex challenges require coordination.

- Redirect technology, don't (necessarily) reject it. Rather than prohibiting AI or conversely accepting surveillance capitalism uncritically, we need to interrogate who controls technology, who benefits, and how we can redirect it toward fairness. The question isn't necessarily “should we use tech?” but "how do we ensure tech serves communities?" And if it doesn’t serve us, we should definitely bin it.

- Coexistence over false binaries. Resist simplistic either/or framing like centralised versus decentralised, individuals versus populations, scientific evidence versus lived experience. The goal is an achievable and sustainable equilibrium, not being right or victorious.

- Justice and sustainability. Attend to power, colonialism, and structural oppression - not as add-ons but as central to understanding and addressing challenges.

These films aren't escapist fantasy. They're imaginative rehearsals for futures we could actually build, if we keep these principles at the forefront of how we think and act. Optimism isn't naivety about how bad things are, but insistence that transformation remains possible through collective action and relationships. As someone who teaches people who shape health systems and who researches health equity, that's the kind of hope I need to sustain myself - and the hope I want to help others cultivate too.

The climate emergency is intensifying, social inequities continue to deepen, and systems of care are under ever more strain.

And yet.

Humans and robots plant gardens together. Communities resist expansionist extractivism and build alternatives. Young people undermine monopolies. The enterprise is never complete, the endpoint is never guaranteed, but the possibility of a better future persists. That's solarpunk's essential message, and it's one I'm going to carry forward.

Read the Solarpunk films list on Letterboxd

This post first appeared on Harris-Roxas Health

Finding your tribe: Why Australia’s social media ban gets it wrong

Australia’s social media ban for under-16s is a classic example of narrative driving policy rather than evidence. Facing a complex problem, the Albanese government has leapt to a simple solution that feels decisive rather than grappling with messy trade-offs. The teen social media ban is exactly this kind of policy on the hoof.

The advocacy group 36 Months has been focal to pushing this ban, backed by high-profile endorsements from the Prime Minister. Yet as Crikey recently revealed, while 36 Months accused critics of being in big tech’s pocket, they were quietly lining up corporate sponsorships, eyeing global expansion, and developing their own AI tools to sell. This advocacy has manufactured urgency around a policy that mischaracterises what’s at stake.

Social media platforms have genuine problems like algorithmic amplification of harmful content, privacy violations and surveillance, addictive design features, and the brainrot inherent letting algorithms determine what you see. These issues arguably accrue more harmfully amongst those older than 16, but that’s a digression.

The potential harms of social media don’t exist in isolation from benefits however, particularly for young people navigating identity formation and seeking community beyond their immediate geography. I think back to Twitter in the early 2010s. It connected me with people I’d never have encountered otherwise during a fairly isolated time in my life, and helped me find my tribe. Twitter wasn’t perfect, and it’s certainly terrible now, but there were meaningful benefits for me.

For LGBTQIA+ young people, neurodivergent people, or teenagers passionate about niche interests, these platforms offer lifelines to communities where they feel they belong. And that’s been cut off precipitously, with no thought, and no voice afforded to those groups.

People with disabilities who are over 16 are also finding themselves affected. They’re funnelled through inaccessible verification system, like facial recognition a proof of age tools that don’t work and aren’t accessible. For these people social media isn’t entertainment, it’s their primary access to information, community, and participation in public life. This law locks them out too.

We’ve now legislated to deny future generations these pathways to connection and identity formation. The ban assumes that removing access equals protection, but it ignores how young people actually develop resilience, critical media literacy, and the communication and citizenship skills they’ll need as adults (and that many people aged over 16 lack).

For policy to be workable, let alone good, requires weighing harms and benefits, considering unintended consequences, and learning from implementation challenges elsewhere. Something like an equity lens, a human rights impact assessment or health impact assessment would have identified all these issues in advance.

Instead we have politics masquerading as protection, wrapped in a rhetoric of parental anxiety and delivered with irresponsible speed. Our teenagers, and the communities they’re finding, deserve better than harmful theatre.

This post first appeared on the Harris-Roxas Health blog.

Image: “Group selfie” Creator: Pabak Sarkar Year: 2014 Format: Digital still photograph Rights: CC BY 2.0 Source: Flickr

Wellbeing for Future Generations: What Will It Take to Embed Health Impact Assessment in Australia?

Yesterday I joined more than forty people at a workshop that explored a question that has haunted my professional life for the better part of two decades: how do we move health impact assessment (HIA) from episodic enthusiasm to genuine, ongoing practice?

The Wellbeing for Future Generations: Lessons from Wales and Building HIA Capacity in Australia workshop was jointly organised by the Cities Institute and the International Centre for Future Health Systems at the University of New South Wales, and was convened by A/Prof Fiona Haigh and Dr Jinhee Kim. It focused on the lessons from Wales' remarkable journey toward legislating HIA, combined with reflections from Australian practitioners about how they’ve navigated the changing use of HIA in Australia. What emerged, for me, wasn't just a comparison of two countries, but a deeper conversation about time, fear, and the architecture of institutional change.

This matters because decisions about transport infrastructure, housing developments, planning, and social programs all shape (costly) health outcomes, but health considerations remain marginal in these processes.

The tide turns

There's a palpable sense that interest in HIA is having a resurgance in Australia. After pioneering work in the early 2000s, Australia’s HIA use gave way to what Fiona today described as "fragmented and champion-driven" activity.

However we're seeing renewed momentum. EPA Victoria is doing focused work on HIA, the enHealth guidelines are being updated, conversations about integration with planning are occurring in different jurisdictions, there seems to be increased receptiveness from local government to consider wellbeing and health across a range of activities.

The tide seems to be coming back in.

But tides are cyclical. The crucial question isn't whether we're experiencing renewed interest; it's whether we can institutionalise approaches that persist after champions move on, when political priorities shift, or when the next public health crisis demands attention.

This is where Wales has done so well but also gives us plenty of insights, not as a template to copy, but as a case study in patient institution-building.

Eight years: playing the long game

Professor Liz Green's keynote traced Wales' path from the Well-being of Future Generations Act to the statutory HIA requirements coming into force in April 2027, which is described in more detail on the Wales Health Impact Assessment Support Unit website.

One detail from Liz’s talk stood out: it took eight years from focused advocacy to the legislation being enacted.

This temporal dimension matters profoundly, but sits uncomfortably with the rhythms that drive most of our work. Media cycles operate in days. Political attention spans in weeks or months. Electoral cycles in three to four years. Research funding rounds in annual competitions. But meaningful institutional change, the kind that shifts how organisations and systems routinely operate, moves on different timescales.

Wales has embedded long-term thinking as one of its five ways of working within the Well-being of Future Generations Act (2015). This detail matters. The recognition that sustainable development, health equity, and genuine stakeholder participation require longer-term horizons is baked into how the Welsh Assembly sees its role, and sees itself as distinct. The question for Australia is can we sustain advocacy and capacity-building efforts across timeframes that outlast individual politicians, program managers, or funding cycles?

Fear, trust, and the culture challenge

Perhaps the most important observation from the presentations and panel discussion was about fear. Fear of scrutiny. Fear of loss of control. Fear that HIA will slow decision-making, expose uncomfortable truths, or empower communities to challenge projects that authorities have already decided. The panel, made up of Liz, Fiona, Jinhee, Kelly Andrews from Healthy Cities Australia, and Dr Emma Quinn from the NSW Ministry of Health, had a wide-ranging discussion. One idea that was suggested was that legislation can counter this emotional, fear-driven response by creating statutory obligations that override individual reluctance.

I’m unsure about this. Does legislation alone ever really change culture, or do people find ways to subvert intent while technically complying? The Welsh model includes transparency requirements, publication obligations, and potential for judicial review—mechanisms designed to make perfunctory compliance more difficult. Yet even with these safeguards, there's recognition that building genuine commitment requires action beyond legal mandates.

This is where recent work applying implementation science frameworks to HIA may be relevant. An international team led by Dr Tara Kenny and Dr Monica O’Mullane from University College Cork (disclosure: including me!) used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to map barriers and facilitators to HIA’s adoption across five domains:

- the innovation itself (HIA as a method),

- outer setting (political and policy context),

- inner setting (organisational capacity),

- individuals (knowledge and attitudes), and

- process (how implementation unfolds).

What implementation science might add

The Kenny et al. review synthesises evidence from 45 studies, revealing patterns that could inform a revamped Australian approach to HIA’s use. Three findings stand out for me.

The first thing is that the early stages of HIA, screening and scoping, are critical not just for technical and procedural reasons, but because this is when critical decisions get made about whose voices matter, what impacts get attention, and how equity will be focused on. The paper suggests that "HIA implementation that encapsulates HIA’s core values of equity and participation require attention at the earlier stages of the HIA and may be difficult to retrofit post scoping." This has pretty far-reaching implications: if we're still serious about participatory, equity-focused HIA, we need to resource and scaffold these early phases differently.

The second issue is that capacity challenges operate across multiple levels and domains simultaneously. It's not just about training individuals to conduct HIAs, or even about developing organisational resources and in-house infrastructure. It's about supportive policy environments, intersectoral partnerships, access to data, alignment with existing impact and policy assessment processes, and broader public health advocacy that creates awareness of the broader determinants of health. The review identifies strategies spanning all five CFIR domains, from clarifying HIA's relative advantage over other assessment tools, to building networks and partnerships, to ensuring adequate funding and dedicated staff.

Third and most fundamentally, the review concludes that “building wider HIA support, awareness, and capacity essential to progressing HIA is dependent on wider public health advocacy and addressing challenges specific to HIA as a method and tool.” In essence, HIA institutionalisation isn't a narrow technical project. It’s embedded within broader efforts to advance Health in All Policies approaches, strengthening understanding of the determinants of health and wellbeing, and shifting how we make decisions about policies, programs, and projects that shape population health.

No wonder it’s been difficult. It involves far more complexity than most simple “innovations”. Yet the alternative, where we continue to make decisions that deliberately or inadvertently exacerbate health inequities, carries its own costs These costs remain largely invisible because we don't systematically assess them and don’t hold people to account for them.

Toward adaptive institutionalisation?

At the end of the workshop, and thinking about Tara’s paper on HIA and implementation science, I came up with an idea I want to explore further: a model of adaptive institutionalisation for HIA in Australia.

Rather than pursuing a single pathway, whether that's a mandate, capacity building, or voluntary adoption (and HIA has always taken heterogeneous forms), what I’m calling an adaptive institutionalisation approach would recognise that different strategies suit different contexts and phases of readiness. This approach acknowledges that political windows of opportunity are unpredictable but can be prepared for. It focuses on capacity building strategies that work with, rather than against, political cycles and extant institutional cultures.

Thinking about CFIR's process domain, this might involve:

Assessing context before acting

Rather than simply following the stepwise HIA procedures uncritically and unconsciously, there may be value in systematically appraising where support and momentum already exists within different contexts, what potential champions already exist and how they could be linked to the HIA process, how HIA timing could align with decision making processes (and how the HIA could be tweaked if it doesn’t align), and what broader policy opportunities could be leveraged. Many experienced HIA practitioners do these things routinely (often due to past failures and errors) but they need to be signposted, made explicit, and acknowledged in HIA guidance.

Staged implementation that matches readiness

Different jurisdictions, sectors, and decision-making contexts sit at different points along the HIA implementation journey. Some might be ready for integration with existing assessment processes. Others need much more foundational awareness-raising of enabling concepts. Others still might benefit from demonstrations of HIA internally that build trust and show practical value. We’ve had to do all of these at different times in New South Wales, but the approach has often been tacitly (and tactically) adaptive rather than guided by a framework.

Attending to timeframes

We need to focus on multi-year strategies that might survive electoral and funding cycles, while also identifying a few short-term wins that build momentum and demonstrate value. Timing and timeliness has been a recurrent theme in HIA effectiveness research. Wales' eight-year journey (within its even longer twenty year journey) suggests we need patient institution-building alongside responsive opportunism. We’ve been doing this within the HIA field, but sometimes not owning up to it explicitly or publicly.

Building trust

Tara’s review emphasises transparency throughout the HIA process, rigorous methodology, and clear documentation of decision-making as essential for building trust in HIA as a process and practice. This matters because it's the foundation for addressing the fear and resistance issues mentioned above that legislation alone can’t overcome.

Conceiving of HIA capacity as part of broader health equity infrastructure

Re-connecting HIA existing health equity initiatives, Health in All Policies approaches, Healthy Cities networks, and cross-sectoral partnerships. This is being done anyway, but it can leverage existing action and make sure that health promotion remains at the heart of HIA along with health protection.

What this means in practice

For those of us working on HIA in Australia, I’ve been reflecting on yesterday’s workshop and I think there are several implications:

- We need to get serious about the early stages of HIA (screening and scoping), recognising these as moments where equity and participation get embedded or excluded.

- We need to map the Australian landscape more systematically. Where is momentum building? What existing assessment and planning processes might HIA enhance or complement? Where do champions exist, and what support do they need? Which policy windows are opening, and how can we prepare to move when they do? (I feel like this is constantly changing, so knowledge that’s derived ad hoc gets out of date quickly)

- We need to develop and revamp resources and guidance that support context-sensitive adaptation rather than prescriptive standardisation of HIA processes.

- We should document and share both successes and challenges more systematically. The evidence base for HIA effectiveness in Australia is relatively good, but we still need honest and public reporting about what didn't work and why, not just spin or examples we’d like to showcase.

- We need to (re)connect HIA advocacy and capacity-building with broader public health movements in Australia for health equity, sustainable development, and participatory governance. HIA isn't an end in itself, it's a way to get to better decisions that protect and promote population health and equity.

The question we left with

As I was facilitating the panel discussion towards the end of the workshop, I posed a thought experiment: imagine we reconvened in three years to find HIA genuinely reinvigorated in Australia, with more widespread use, demonstrable impacts on health equity, energy and momentum. What would have happened to get us there?

The answers pointed toward both top-down enablers (policy frameworks, funding, legislation) and bottom-up drivers (community demand, practitioner networks, demonstrated value for different sectors). The discussion also mentioned the need for both quick wins (showing value and responsiveness) and more slow, patient institution building (developing sustainable infrastructure).

I'd add one more element to what was discussed, drawn from our conversation about time and Wales' experience. We need to have realistic expectations about the temporal rhythms of institutional change. Eight years from advocacy to legislation. Twelve years before that to build capacity, develop guidance, train practitioners, and shift organisational cultures.

This doesn't mean twenty years of waiting. It means strategic, sustained effort across multiple fronts and building on the work that’s already been done over decades in Australia to further develop capacity, seize opportunities, create demand, (continuing to) demonstrate value, form and expand partnerships, shift narratives, and yes, when circumstances align, pursuing legislation and regulatory frameworks.

The tide may be coming in, but tides don't build seawalls (to torture a metaphor). We still need intention, resources, coordination, and time.

The question is whether we're prepared for the long work of adaptive institutionalisation. If we can be patient enough for the timeframes involved, strategic enough to work across multiple levels and domains, and committed enough to sustain effort when the returns won’t be immediately evident.

Wales shows it's possible. Implementation science may give us ways of formalising and describing the hard work of institutionalising HIA that’s already been undertaken. In Australia there are still meaningful challenges and opportunities. What happens next depends on whether we can translate enthusiasm into the kind of sustained (generational?), multilevel effort that genuine institutionalisation will require.

Thanks

Many thanks to all participants at the 1 December workshop participants, particularly Liz Green for sharing Wales' experience, and to the panelists Kelly Andrews (Healthy Cities Australia), Dr Emma Quinn (NSW Ministry of Health), A/Prof Fiona Haigh (UNSW International Centre for Future Health Systems), and Dr Jinhee Kim (UNSW Cities Institute) for their insights. The workshop was jointly organised by the Cities Institute and the International Centre for Future Health Systems.

References

CFIR Research Team. (2025). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Center for Clinical Management Research. https://cfirguide.org

Kenny, T., Harris-Roxas, B., McHugh, S., Douglas, M., Green, L., Haigh, F., Purdy, J., Kavanagh, P., & O’Mullane, M. (2025). Routemap for health impact assessment implementation: Scoping review using the consolidated framework for implementation research. Health Promotion International, 40(3), daaf080. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daaf080

This post first appeared on the Harris-Roxas Health blog.

David Lynch was a visionary in an era bereft of them

I’ve read a few things about Lynch over recent years that expanded my appreciation his impact. I thought others might be interested in them following his recent death.

Agency and Imagination in the Films of David Lynch: Philosophical Perspectives is an interesting companion to eight of his films and Twin Peaks: The Return.

Deviant obsessions: how David Lynch predicted our fragmented times - Phil Hoad in The Guardian.

Another Article about David Lynch - Patryk Chlastawa in The Point

Our doubles, ourselves: Twin Peaks and my summer at the black lodge - Linnie Greene’s reflections on her time in Lynchian darkness

This book is esoteric and academic but discusses his impact on transmedia aesthetics in a novel way - Networked David Lynch: Critical Perspectives on Cinematic Transmediality.

This podcast (in French) had an interesting discussion about Lynch.

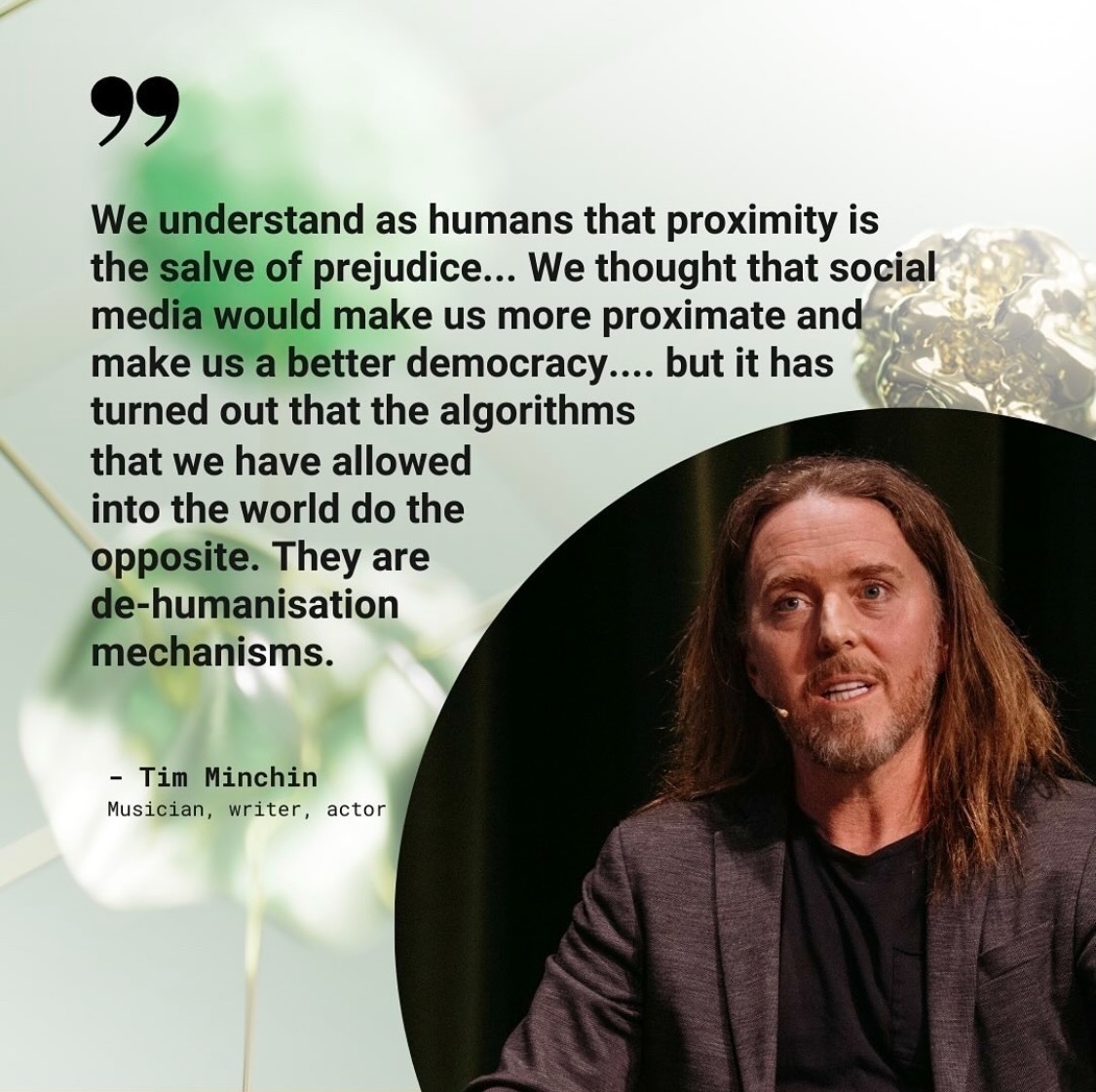

Getting free from the slop machine

He’s half right. Manipulation by recommendation engines and algorithmic oppression is an extant threat that’s changing our relationships and our politics.

But social media - interactive technologies that facilitate the networked sharing of information - can be emancipatory. It can expand our worlds in real ways. That sounds Pollyanna-ish until you recall that we’ve experienced that potential ourselves. Made new friends. Seen things in new ways.

It wasn’t always this way

One of my kids was recently quizzing me about Mastodon, and he pulled me up when I said I like the chronological feed.

“What does that mean? If there’s no algorithm, how do they know what you want to see?”

I realised he’s never known a chronological social media feed. Twitter, Instagram and Facebook abandoned theirs before he was born. The idea that all I see are the accounts I follow, and that I see everything they post, in the order they post, broke his brain a bit. He didn’t like it.

“You might also like” this slop

But the recommendation algorithms aren’t working like they used to either (if they ever really worked at all). Instagram is allowing you to “reset” your recommendation algorithm. Even though they have hundreds of thousands of data points about you, they’re recommending things that you’ve already long-forgotten. Or worse, that you wish you could forget.

Beyond blocking or unfollowing accounts, there aren’t many ways for us as users on algorithm-driven platforms to control the slop we’re fed. In fact most platforms are doubling down on the slop, serving up content from accounts you never followed in an effort to drive up fake engagement metrics. I don’t know if you’ve checked Facebook lately, but the dead internet is real and your relatives are trapped in it.

That highlights a tension we all experience. We all know our privacy is being invaded and our data linked by these recommendation algorithms. We don’t like the idea that we’re living in filter bubbles where something else decides what we see, but we can’t imagine anything else possible.

What instead?

This also made me consider a major upside of the fediverse that we don’t promote enough: the best recommendation algorithm is another human, and on the fediverse that’s all we have.¹ There are still human-driven ways to encounter novelty, and to escape the flattened world served up to us by algorithms.

These are some of the ones I use:²˒³

- For academic reading: The Syllabus is expensive, but it offers genuine insights into different fields. It’s expanded my reading and thinking.

- For links: Metafilter is still the most venerable and reliable source of web-based surprises.

- For films: Letterboxd has a “films like this” algorithm, but that’s about the extent of the recommendations you’ll find. It’s still what your friends watch, listed in the order they watched them.

- For photos: Pixelfed or even classico Flickr will make you happier than Instagram.

- For fiction: BookWyrm eclipses the bizarro, astroturfed morass of snark and spin that is Goodreads. Real humans talking about the books they’ve read, and they’re on the fediverse too.

- Feeds: Good old RSS feeds. These can be hard to get started with, but people like Molly White have shared the feeds they subscribe to, which you can treat like starter packs (and remember that podcasting is basically audio RSS).

These options often have a cost in money or time, essentially because they involve work instead of harvesting your data and mining your attention. If you look at Facebook, TikTok or YouTube you can see that what appears to be free has a cost.

A slop-free existence is possible, but it takes a bit of work.

- Yes, I know there are bot accounts, but you have to follow them.

- You’ll notice that Bluesky is nowhere on the list. That’s because even though it’s not be the latter-day 4chan that X-the-everything-app has become, it still relies on graph neural network recommender engines. It’s still slop. The ingredients just aren’t as bad - yet.

- Social video is tough and not something I know enough about. I’m not a big viewer of YouTube-like platforms. Peertube would be worth trying, but I don’t use it much. YMMV.

“We are leaving a trail of devastation through the earth with our daily lives and we don’t care about it yet.”

I was interested in this speech by Ilona Kickbusch on the challenge of trying to create healthier societies during the polycrisis.

One of her slides jumped out at me, contrasting Goran Dahlgren and Margaret Whitehead’s longstanding model of the determinants of health with a cyclone:

This image has been central to public health messaging since the earliest stages of my career. Seeing it spun into chaos seems like an appropriate metaphor for the challenges that my field faces.

Ilona also quoted German Economics Minister Robert Habeck, who I think has it right:

“…when we live our everyday lives, when we fill up our cars, when we slather our mince on the mince roll, we are always on the side of the good guys. Only people who have never been in a pigsty can believe that. We are leaving a trail of devastation through the earth with our daily lives and we don’t care about it yet.“

Robert Habeck, 2022

This post originally appeared on the Harris-Roxas Health blog.

Daily shisha use: the tobacco control niche that’s not so niche any more

Between 1.8% and 3.6% of smokers use shisha daily across Australia, up from 1% just three years ago.

That’s the shocking result from the 2022-2023 National Drug Strategy Household Survey that was released Wednesday. It deals with a range of alcohol and other drug use, but I was interested in the data on tobacco use. In particular, what’s been happening with shisha use.

The 2022-3 survey results show a dramatic increase in the daily use of shisha in Australia over the COVID-19 period from 1% of smokers in 2019 to 2.7% only three years later.

Keep in mind that this is daily use. 45 minutes of shisha use equates with more than 100 cigarettes, so this represents a marked increase in overall tobacco consumption for people in this group.

We can be fairly confident this increase is real and that the rate is between 1.8% and 3.6%. The 95% confidence intervals for the 2022-3 survey are 0.9% and the rate of standard error is 17.7% (RSE, generally <25% is considered reliable for most practical purposes).

This challenges assumptions made by many working in tobacco control and public health that shisha use is infrequent.

We also know that use isn’t distributed evenly. 2.7% of all smokers may seem like a small proportion, but this increase disproportionately affects Arabic speaking communities and populations, people living in cities and regional centres, and other migrant groups.

This is also consistent with focus groups that Dr Lilian Chan and I conducted for the Shisha No Thanks project in 2022. People who used shisha told us that their use had intensified through the COVID lockdowns, but that this increase had continued afterwards and was increasingly complemented with e-cigarettes use.

We need to increase our focus on:

- increasing awareness of the harms of water pipe use (this remains low)

- providing avenues for quitting that are tailored to shisha users

- making sure use at food venues complies with existing laws

- enforcing and retail import conditions more consistently.

Sources

AIHW. (2024). National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey/contents/technical-notes

Do you experience tinnitus?

I read this study about a soundscape and CBT app that sounds promising

Your mileage may vary but it seems worth sharing.

Fifteen Years of Equality? Disability in Australia after the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Fighting against the segregation of people with disabilities, giving a more meaningful voice to people with disabilities, and making sure the NDIS doesn’t become a (more) broken funding model. These were some of the issues discussed during a fascinating panel discussion last night that was organised by the UNSW Disability Innovation Institute to mark the International Day of People with Disability.

The discussion explored what progress has been made in the fifteen years since the adoption of the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – or lack thereof. The panel included June Riemer, Dr Alastair McEwin, Rosemary Kayess, Fiona Mckenzie and Prof Julian Trollor, and was facilitated by Nas Campanella.

The CPRD played a major role in shifting the perception of people with disabilities from the subjects of medical treatment and charity, to full members of society with human rights.

One of the strongest themes from the discussion was the need to normalise and support people with disabilities to participate in all aspects of life and to end segregation. The content of the Convention remains relevant – and a lot of it remains unrealised:

The purpose of the present Convention is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) Article 1

As the incoming Disability Discrimination Commissioner Rosemary Kayess summarised, “we’ve got to stop focusing on the diagnosis and start focusing on the processes to support people to participate… Let’s stop with the catchphrases and talk about disability like grown-ups.”

Fifty Years on, the Whitlam government's Community Health Program is more relevant than ever

On Friday I had the privilege of attending a forum Celebrating the Whitlam Community Health Program: Lessons for the Future and participating on a panel at the Whitlam Institute.

The forum was the culmination of an ARC-funded Project looking at Contemporary lessons from a history of Aboriginal, women’s and generalist community health services in Australia 1970-2020, which involved more than a dozen investigators from nine universities and partner organisations.

The Community Health Program

The Community Health Program was established in 1973 and within three years it had funded over 700 projects, including community health centres, Aboriginal medical services, and women’s health centres.

Gough Whitlam, in a 1993 keynote address to the Australian Community Health Association’s National Conference in Adelaide in 1993Communities must look beyond the person who is sick in bed or who needs medical attention. The (Hospitals and Health Services) Commission will be concerned with more than just hospital services. The concept and financial support will extend to the development of community-based health services and the sponsoring of preventive health programs.

Even though the program was gouged by later governments many of the services funded still exist. For example I’ve worked with the Liverpool Women’s Health Centre this year, which was founded by a collective in 1975 and funded through the CHP.

The vision of the CHP remains relevant today: ensuring that people can have access to relevant,meaningful multidisciplinary care in the community. When the CHP was conceived in the early ’70s it sought to meet the preventive care needs, to address inequalities, to reduce demands on hospital emergency departments, and tackle rising rates of chronic disease – issues which we have gone backwards on since.

The presentations and panel discussions highlighted that while the community health sector remains dynamic, Commonwealth engagement with the sector has been erratic. There’s a need to return governance to communities, reduce the variability in services offered by community health between states and regions, and to return to block funding rather than project funding. Primary Health Networks are well placed to tackle these issues, and to foster the kind of resilient local service systems that we’ll need to address environmental, social and economic shocks in the near future.

Thanks to all involved for a very thought-provoking afternoon.

Project team

Researcher and Project Manager

Dr. Connie Musolino, University of Adelaide.

Chief Investigators

- Professor Fran Baum AO, Stretton Health Equity, University of Adelaide.

- Associate Professor Tamara Mackean, Flinders University.

- Professor Warwick Anderson, The University of Sydney.

- Emeritus Professor Colin MacDougall, Flinders University.

- Professor Virginia Lewis, La Trobe University.

- Associate Professor David Legge, La Trobe University.

- Dr. Toby Freeman, University of Adelaide.

Partner Investigators

- Patricia Turner AM, CEO of the National Aboriginal Community ControlledHealth Organisation (NACCHO).

- Denise Fry, Sydney Local Health District.

- Paul Laris, Paul Laris and Associates.

- Tony McBride, Tony McBride & Associates.

- Jennifer Macmillan, La Trobe University.

Researchers and Students

- Dr. Helen van Eyk, University of Adelaide.

- Dr. James Dunk, The University of Sydney.

- Abdullah Sheriffdeen, Flinders University.

- Jacob Wilson, Flinders University.

Understand who this person was, who they are, their challenges, their triumphs: What leads to brilliant aged care?

Even though many aged care services don’t provide the care that older people and carers need and want, some do it much better than others. Why?

That’s the question colleagues from WSU, UNSW, SESLHD, SWSLHD, RCSI and I explored in an open access article that explores these questions, led by Associate Professor Ann Dadich.

Rather than focusing on the substantial and systemic problems facing aged care, this study examined brilliant aged care — practices that exceeded expectation.

There are many insights into what can lead to brilliant aged care, which can be broadly categorised into:

- deep understanding of the older person

- more than a job

- innovative practices

- permission to reprioritise.

Some of the best insights came from the artefacts that people were asked to bring to the interview, which were items (e.g. photos, items, artworks or other objects) that reflected brilliant aged care for them. These artefacts opened up new lines of discussion and new ideas, for example:

“people in the late stages of dementia are like an oyster, one of the ugliest, kind of gnarled shells you could possibly think of. There are so many beautiful shells in the world. The oyster isn’t one of them and yet when you open it up, it has this extraordinary little pearl inside it and that’s what we need to find in every older person. Every older person, no matter … what their state of health or wellbeing, still has that pearl that is that beautiful human being inside them and it’s our job, not their job, it’s our job to open that up and find that pearl.” (Grace)

There’s a lot more in the open access article – take a look.

Dadich, A., Kearns, R., Harris-Roxas, B., Ni Chroinin, D., Boydell, K., Ní Shé, É., Lim, D., Gonski, P., & Kohler, F. (2023). What constitutes brilliant aged care? A qualitative study of practices that exceed expectation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, online first. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16789

Is Mastodon a hostile place?

I read a useful post by Erin Kissane, where they asked people on Bluesky about what their negative experiences of Mastodon had been. I recommend you read it.

The main issues reported by people were that:

- they got scolded, usually for failing to use content warnings

- that they couldn't discover or easily search for people to follow

- it's confusing to have multiple instances

- it's too serious

- people are being denied features like reposts in the name of safety, rather than being treated by adults.

Separate to Erin's work, I asked a similar question on Bluesky last week and received a much smaller, but consistent set of responses.

We should take these issues seriously. Mastodon should continue to aspire to be a safe place, in particular people who are marginalised on the basis of race, gender, sexuality, disability and poverty. Many of the complaints identified by Erin are, at least in part, reflective of deep concerns about the safety of users that have guided the development of the platform.

However we have to acknowledge that people have been driven off. Many of those who've gone would make Mastodon a richer, more diverse and more interesting place. I changed instances last week and in the process I unfollowed several hundred accounts that I used to interact with, but who haven't posted for at least six months. I miss a lot of these people and we shouldn't callously dismiss their departure.

Perhaps we need to chart a middle path between safety and approachability.

The way we make and keep Mastodon, and the fediverse more generally, safe is by not tolerating bad faith nonsense. Agonising over this is a weakness that villains exploit, and which has systematically ruined corporate social media (though their owners have done a good job of ruining that all on their own).

I confess that I get frustrated with complaints about content warnings (CWs). Nobody has a right to my eyeballs or my thoughts. Screaming into the void is one thing, but you don't have the right to pour your negative emotional state into my brain.

The caveat to this, and it's a critical one, is that many people of colour and trans people have said that they've been lectured to use content warnings when complaining about the people, structures and processes that oppress them (Often referred to as a home owners association – or HOA – mindset. HOAs are themselves a U.S. term, so its usefulness as shorthand is pretty limited).

We have to believe these people. Their experiences are real and their perspectives are legitimate. The need to listen to these people precisely the we can't allow this variation of bad-faith sealioning to proliferate, and for CW scolding to be weaponised.

Again this speaks to the need for a middle path between safety and approachability.

Similarly, maybe people on the fediverse should throttle back on “you need to” posts if someone doesn't use a CW or include alt-text on an image. I like those norms, they actually help inclusivity, but they're possibly at the expense of being welcoming and allowing people to make good-faith mistakes.

None of these issues are resolved by technical affordances. A repost button that allows to dunk on other people would be neither more welcoming nor safer.

The middle path between safety and approachability will be charted by how we act.

Ben Harris-Roxas Website | Publications | Mastodon

Equity in Primary Health Care Provision: More than 50 years of the Inverse Care Law

I guest edited a special issue of the Australian Journal of Primary Health with Dr Liz Sturgiss that reflects on more than 50 years of the Inverse Care Law.

The Inverse Care Law was first coined by Julian Tudor Hart in 1972 to refer to availability of good medical and social care varying inversely with the needs of the population served .

As we note in the editorial:

…we cannot forget the importance of income inequality as one of the primary manifestations of disadvantage. Poverty remains one of the principal determinants of how the inverse care law plays out in primary health care and it is a cross-cutting issue that affects all disadvantaged groups to varying degrees. All approaches to improve the access to primary care would benefit from specific attention to how the needs of those living in poverty are served.

The special issue includes a range of articles on the Inverse Care Law itself, Aboriginal and First Nations health, care for transgender people, access for people from culturally diverse backgrounds, and general practice. Most are open access – please take a look.

References

My friend comes uninvited

It comes instead when I am fighting not an open but a guerrilla war with my own life, during weeks of small household confusions, lost laundry, unhappy help, canceled appointments, on days when the telephone rings too much and I get no work done and the wind is coming up. On days like that my friend comes uninvited. (Joan Didion, 1979)

It's hard for me to remember a time before migraine. My first one was when I was thirteen, after a day of what I later came to recognise as prodrome and aura followed by disembodied but all-consuming pain.

Everyone's migraine is different, but that doesn't stop people from recommending treatments based on their own experiences. My migraine is known as “classic migraine” or migraine with aura. I see see points of colour, become sensitive to light, get confused, and start speaking gibberish. This is known as “word salad”, which doesn't really do justice to the sensation of one's mind being unable to select the right word, of being decoupled from the ability to use language.

Migraine is the second most common cause of disability, after back pain (Steiner et al., 2020). Its causes remain elusive, though it seems likely that it's a collection of neurological and neurovascular disorders. I think (hope?) it will always be somewhat unknowable. For a while my brain doesn't work and I'm incapacitated, and then it passes. It feels like something that can't be fully known.

I've become better at managing my migraine over the years, which is simply to say that I've become better at recognising the early signs. I've tried drugs, but the trade-offs stack up quickly. Weighing up side effects and the risk of migraine changes when it's been months or, once, years since my last migraine.

I had a bad one yesterday, my worst in quite a while. I'm still fuzzy and depleted.

People who experience tinnitus are often advised to undertake cognitive restructuring, to think of tinnitus as a friend who's always with them (Fuller et al., 2020). I don't think I'll ever be able to think of migraine as anything other than a tormentor.

If there is a good aspect of migraine it's in its passing. Nausea intensifies, and for me, suddenly, relief. The weight is removed. Light becomes less harsh. Colours change. Language returns.

Sources

Didion, J. (1979). The White Album. Simon & Schuster.

Fuller, T., Cima, R., Langguth, B., Mazurek, B., Vlaeyen, J. W., & Hoare, D. J. (2020). Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012614.pub2

Steiner, T. J., Stovner, L. J., Jensen, R., Uluduz, D., Katsarava, Z., on behalf of Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache. (2020). Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 21(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0

Ben Harris-Roxas Website | Publications | Mastodon

Evaluation of ‘Shisha No Thanks’ – a co-design social marketing campaign on the harms of waterpipe smoking

An important paper from our Shisha No Thanks! project, led by Lilian Chan, has been published:

This is one of the first published evaluations of a health promotion intervention targeting young people to address the growing global trend of waterpipe smoking. It makes a timely and important contribution that demonstrates that co-design social marketing campaigns can raise awareness of messages about the harms of water pipe smoking among young people of Arabic speaking background.

It’s open access and free to access.

References

“The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need of the population served” – Submit your article to our special issue marking fifty years of the inverse care law

Dr Liz Sturgiss and I are guest editing a special issue of the Australian Journal of Primary Health on “Equity in Primary Health Care Provision: More than 50 years of the Inverse Care Law”.

The special issue will cover a range of topics, including:

- Comprehensive primary health care for specific populations, including

– prison populations

– Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and First Nations

– culturally and linguistically diverse communities

– people living in poverty

– populations experiencing homelessness and unhoused people

– rural and remote health. - Models of care and health services research.

- Team based care and exploration of scope of practice.

- Policy innovations and funding models.

- Community-based responses to the needs of marginalised and oppressed groups.

There’s more information on the special issue and the Australian Journal of Primary Health herehttps://www.publish.csiro.au/py/content/CallforPapers#1. Final submissions are due by 15 July 2022 but we’re asking that people submit EOIs in the form of an abstract by 30 March 2022.

Reflecting on 2021 for the Australian Journal of Primary Health

The past year has also seen significant changes in academic publishing. There has been an emphasis on rapid dissemination of research findings during the pandemic, increasing the prominence of pre-publication manuscripts and reinforcing the need for timely peer review. There has been a significant increase in the volume of manuscripts submitted, including to the AJPH.

At the same time, it is more difficult than ever to find peer reviewers for submitted articles. There has been a significant increase in the pressures on people’s time, through their paid jobs, but also because of juggling caring responsibilities during multiple lockdowns. Many people have been redeployed to support health systems and organisations to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Australian Government’s decision to not provide any financial support to universities during the pandemic has led to thousands of jobs being lost across the sector over the past year, with more losses likely to come. Precarious employment has become even more entrenched and fewer people are in jobs that include service to the profession as part of their roles. This leads to fewer people being able to undertake reviews at the time we need high-quality peer review most.

— Read on www.publish.csiro.au/py/Fulltext/PYv27n6_ED

It’s been a pleasure being an Associate Editor for AJPH, and it was good to have this opportunity to reflect on the pst year with Virginia Lewis and Jenny Macmillan as I’m stepping down.

Ensuring culturally diverse communities aren’t left behind on the road out of COVID

“We are always engaged after there is a problem – never upfront. The damage that has been done is quite severe on the ground and there is a lot of feeling that this is racist”- Randa Kattan, CEO of the Arab Council Australia

Tweet

Croakey published a comprehensive summary of the think tank workshop hosted by the UNSW School of Population Health and organised by my colleague A/Prof Holly Seale. It features some inspiring practical activities led by culturally diverse communities, and the findings of research from across Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria.

“This current pandemic again highlights that there is a critical need to ensure services, communication and efforts and other pandemic strategies are designed and delivered in a culturally responsive way,” she said. Seale stressed collaboration with people from CALD backgrounds, including refugee communities, was critical to improving future pandemic plans as well as continuing ongoing COVID-19 activities.

Engage and empower: ensuring culturally diverse communities aren’t left behind on the road out of COVID